Over 55 Jewish partisans gathered together in New York City on November 6th and 7th to commemorate the enduring legacy they share and to be honored at the Jewish Partisan Educational Foundation’s 2011 Tribute Dinner. Traveling from throughout the United States, many with children, grandchildren and even some great-grandchildren in tow, they reconnected with friends and quickly rekindled the strong bonds that will forever unite them.

The celebration began with a Sunday afternoon reception for partisans and their family members, hosted by JPEF, at the Park East Synagogue. Laughter resonated throughout the space as partisans embraced one another, tears of joy welling in their eyes. For many, this was the first time they had seen one another in over sixty-five years. Allen Small, who traveled from Palm Beach Gables, Florida, was overjoyed to be reunited with Leon Bakst who came from Dallas, Texas.

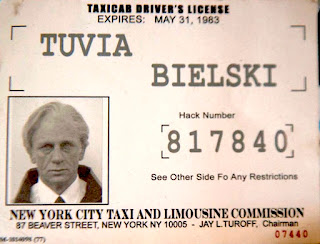

Over 400 guests packed the stylish art deco Edison Ballroom the following evening to formally recognize and honor the courage and sacrifice demonstrated by these Jewish partisans during World War II. Mistress of Ceremonies Dana Tyler, Senior News Anchor for WCBS-TV and actor and Emmy winner Edward Asner, the cousin of partisan Abe Asner, paid tribute to each of the honorees. With their black and white partisan photograph projected on screen, each partisan was individually honored and identified by name, country of birth and the partisan group in which they served. In all there were 23 women and 33 men, representing brigades from Belarus, Poland, Czechoslovakia, the Ukraine, Russia and France. Included among the attending partisans were six married couples, three sets of siblings, a rabbi, a cantor and a mohel.

Guests watched in awe as each partisan, most in their eighties and nineties, stood to accept their honor with the same characteristic strength and determination that empowered them to fight back so many years before.

In his address Asner stated, “JPEF is important because it puts the legacy of the Jewish partisans front and center, as no other organization does. It stays committed to its mission and does not deviate.”

In his address Asner stated, “JPEF is important because it puts the legacy of the Jewish partisans front and center, as no other organization does. It stays committed to its mission and does not deviate.”Lauren Feingold, granddaughter of partisans Dr. Charles Bedzow and Sara Golcman Bedzow also spoke. As the first third generation representative to the JPEF Board, Lauren worked closely with her grandfather, who serves as JPEF’s Honorary International Chairman, to promote the Tribute Dinner and guarantee its success. Like Lauren, many of those involved in the recently formed 3G group, are already working to ensure that young people everywhere are empowered by their grandparent’s examples, and she challenged her peers to join in this quest. She was followed by Charles who spoke movingly to his fellow partisans reminding them that they share a unique and important legacy; one which must be passed from generation to generation.

In a fitting testament to this charge, Cantor Shira Ginsburg, grandaugher of partisan Judith Ginsburg, closed the event with a performance of the song “Who Am I”, about her family and the inspiration of her grandmother’s partisan legacy. As Shira’s beautiful voice filled the room, more than forty third generation teens and young adults raised white candles high, signaling their commitment to keep the flame alive.

JPEF extends its sincere appreciation to event co-chairperons Esther-Ann Asch, Suzanne and Elliott Felson, Kim and Jonathan Kushner and Diane and Howard Wohl for their dedication to ensuring the success of this remarkable event.

Links to press materials about the event:

Jerusalem Post article.

Jewish Week article.

An article in the Algemeiner.

WCBS nightly news video.

More photos from the event on our Flickr page.